The Graphene-Info Newsletter

posted on

May 11, 2021 10:07AM

Hydrothermal Graphite Deposit Ammenable for Commercial Graphene Applications

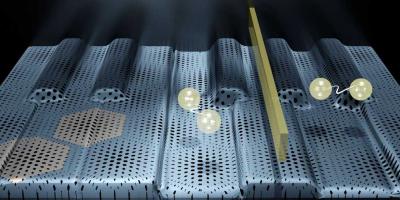

Researchers at ETH Zurich, led by Klaus Ensslin and Thomas Ihn at the Laboratory for Solid State Physics, have succeeded in turning specially prepared graphene flakes either into insulators or into superconductors by applying an electric voltage. This technique is even said to work locally, meaning that in the same graphene flake regions with completely different physical properties can be realized side by side.

The material keyboard realized by the ETH Zurich researchers. Image by ETH Zurich/F. de Vries

The material keyboard realized by the ETH Zurich researchers. Image by ETH Zurich/F. de Vries

The material Ensslin and his co-workers used is known as “Magic Angle Twisted Bilayer Graphene”. The starting point for the material is graphene flakes - the researchers put two of those layers on top of each other in such a way that their crystal axes are not parallel, but rather make a “magic angle” of exactly 1.06 degrees. “That’s pretty tricky, and we also need to accurately control the temperature of the flakes during production. As a result, it often goes wrong,” explains Peter Rickhaus, who was involved in the experiments.

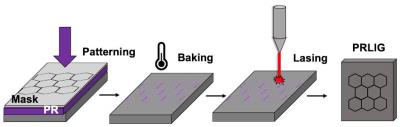

A Rice University team has modified its laser-induced graphene technique to make high-resolution, micron-scale patterns of the conductive material for consumer electronics and other applications. Laser-induced graphene (LIG), introduced in 2014 by Rice chemist James Tour, involves burning away everything except carbon from polymers or other materials, leaving the carbon atoms to reconfigure themselves into films of characteristic hexagonal graphene. The process employs a commercial laser that “writes” graphene patterns into surfaces that to date have included wood, paper and even food.

The new version writes fine patterns of graphene into photoresist polymers, light-sensitive materials used in photolithography and photoengraving. Baking the film increases its carbon content, and subsequent lasing solidifies the robust graphene pattern, after which unlased photoresist is washed away.

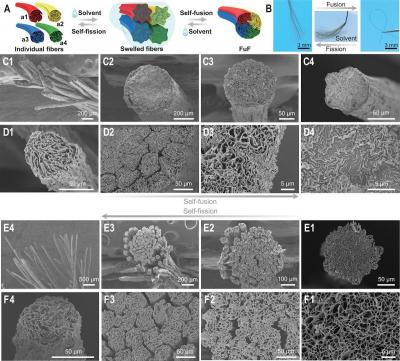

Researchers from Zhejiang University, Xi'an Jiaotong University and Monash University have developed a way to bind multiple strands of graphene oxide together, creating a process that could prove useful in manufacturing complex architectures.

Reversible fusion and fission of GO fibers. Credit: Science

Reversible fusion and fission of GO fibers. Credit: Science

In recent years, materials scientists have been exploring the possibility of making products using total or partial self-assembly as a way to produce them faster or at less cost. In biological systems where two materials self-assemble into a third material, scientists describe this as a fusion process. Accordingly, when a single material spontaneously separates into two or more other materials, they refer to it as a fission process. In this new work, the researchers have developed a technique for creating graphene-oxide-based yarn that exploits both processes.

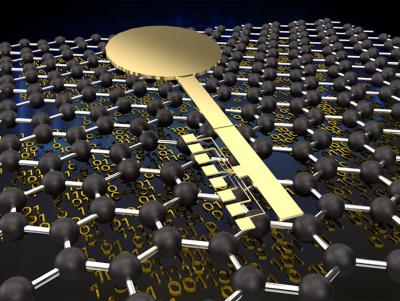

Penn State researchers have designed a graphene-based way to make encrypted keys harder to crack, in an attempt to protect data in an age where more and more private data is stored and shared digitally. Current silicon technology exploits microscopic differences between computing components to create secure keys, but the team explains that artificial intelligence (AI) techniques can be used to predict these keys and gain access to data.

Image credit: Jennifer McCann/Penn State

Image credit: Jennifer McCann/Penn State

Led by Saptarshi Das, assistant professor of engineering science and mechanics, the researchers used graphene to develop a novel low-power, scalable, reconfigurable hardware security device with significant resilience to AI attacks.

In 2018, Sunrise Energy Metals (SRL) and Ionic Industries partnered up and established a JV called NematiQ to develop graphene oxide (GO) membranes for water treatment applications. SRL initially had a 75% stake in the joint venture, before increasing its interest to 83.2% in 2020. Now, SRL announced its plan to take full ownership of NematiQ.

NematiQ has developed a process for manufacturing GO, which can be applied to a membrane support to create a graphene oxide-based nanofiltration membrane (GO-Membrane). The GO-Membrane manufacturing process has reportedly already been demonstrated on commercial-scale industrial equipment.