The future of EV batteries could be found under the sea

posted on

Jul 06, 2021 08:01AM

NI 43-101 Update (September 2012): 11.1 Mt @ 1.68% Ni, 0.87% Cu, 0.89 gpt Pt and 3.09 gpt Pd and 0.18 gpt Au (Proven & Probable Reserves) / 8.9 Mt @ 1.10% Ni, 1.14% Cu, 1.16 gpt Pt and 3.49 gpt Pd and 0.30 gpt Au (Inferred Resource)

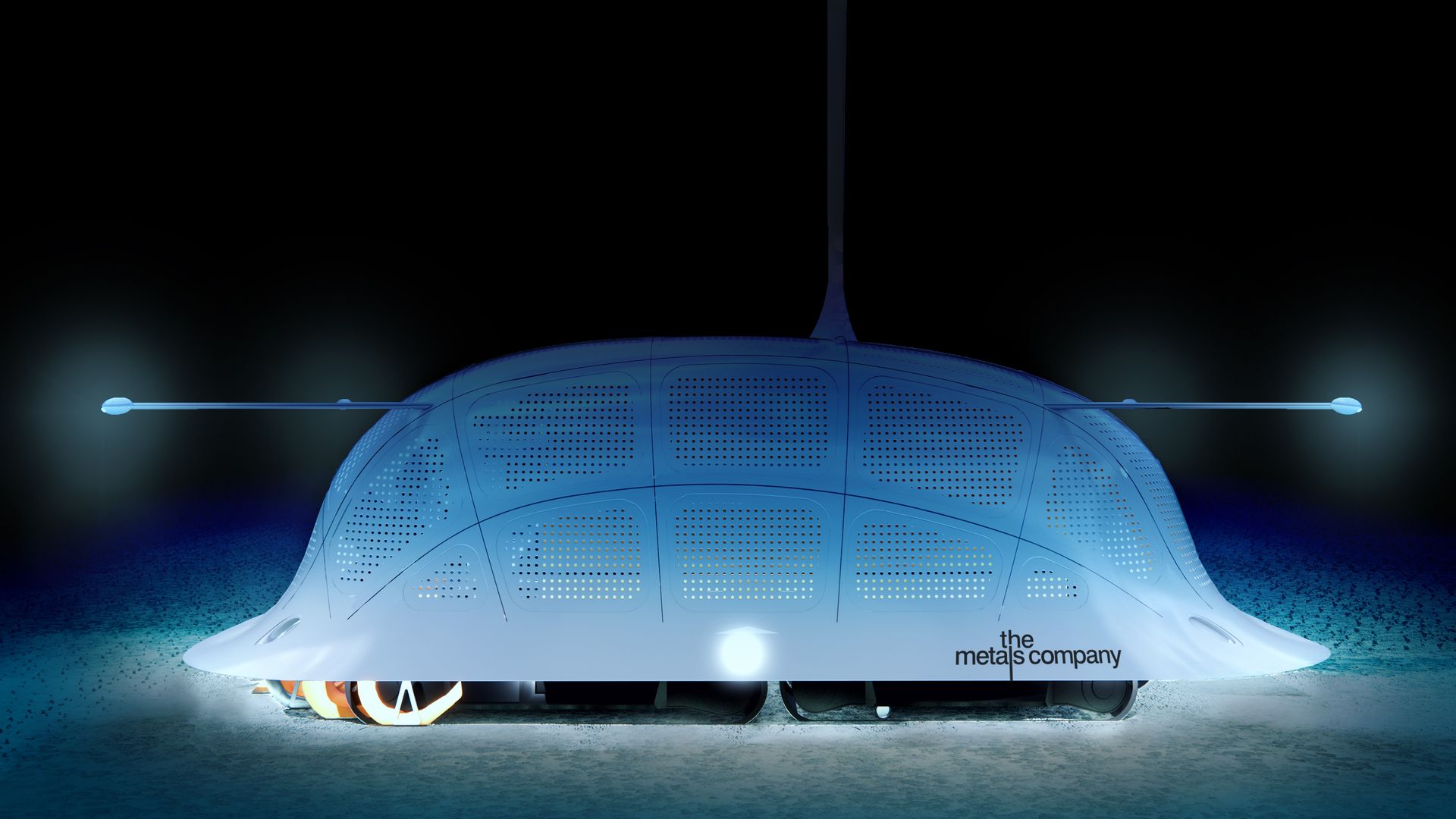

A collector robot gathers polymetallic nodules on the seabed for processing. Photo courtesy of The Metals Company

A collector robot gathers polymetallic nodules on the seabed for processing. Photo courtesy of The Metals CompanyAll the battery metals we need to power a billion electric vehicles could be lying on the floor of the Pacific Ocean — but collecting them and turning them into EV batteries is a major challenge.

Why it matters: It's going to take a lot of batteries to replace the world's gasoline-powered cars with zero-emission EVs. And that will require digging more lithium, nickel, cobalt, copper and manganese out of the earth.

What's happening: The Metals Company of Vancouver claims it has identified a less damaging way to mine battery metals from ancient rocks resting on the seafloor.

Context: Polymetallic nodules are metal-rich rocks formed slowly over millions of years as layers of iron and manganese hydroxides grew around a small shell or rock fragment. Many also contain nickel, copper and cobalt.

How it works: A robotic collector — akin to a giant vacuum — skims designated areas of the seabed, sucking up polymetallic nodules lying amid a thin layer of sediment, before pumping them up to a production support vessel on the surface.

The other side: "Sending gigantic mining machines designed to bulldoze and churn up the seabed is clearly a very bad idea," according to a Greenpeace post.

The Metals Company sees it differently. The rocks are easily removed without blasting, drilling or excavating — traditional ore mining practices that cause deforestation and create toxic waste.

What's next: The company, founded in 2009 as Deep Green Metals, is going public via merger with a shell company called Sustainable Opportunities Acquisition Corporation.

The reality is that the clean energy transition is not possible without taking billions of tons of metal from the planet. Seafloor nodules offer a way to dramatically reduce the environmental bill of this extraction.— Gerald Barron, The Metals Company